Table of Contents

How Your Gut Microbiome Could Impact MS Symptoms | Enbiosis

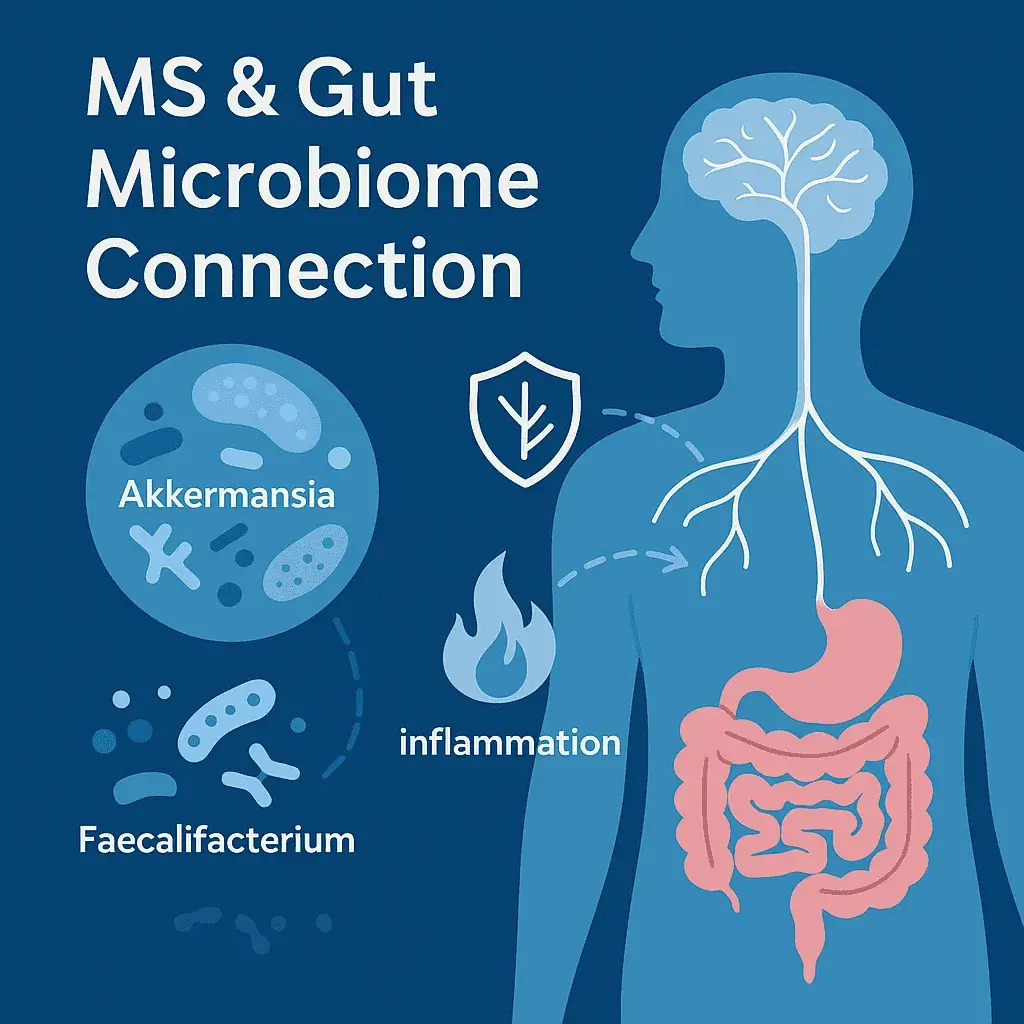

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic and unpredictable neurological condition which affects the central nervous system. It occurs when the immune system mistakenly attacks the protective cover surrounding nerve fibres, known as the myelin sheath. This disrupts vital nerve signals and can lead to long-term damage to the brain and spinal cord MS patients experience a diverse range of neurological symptoms, commonly including fatigue, numbness or tingling sensations in various parts of the body, muscle cramps, stiffness or spasms, mobility difficulties, vision problems, and cognitive changes. These symptoms can vary greatly from patient to patient and depend upon the location and extent of nerve damage. MS can be categorized into different types, which include relapsing/remitting, secondary progressive and primary progressive, each with its own distinct pattern of progression. At present there is no cure for the condition, however there are many treatments available that can help patients to manage their symptoms and slow disease progression. While researchers are still uncertain about the cause of MS, it is generally understood that the condition results from complex interactions between a person’s genetics and certain environmental factors that can influence activity of the immune system. One emerging area of interest is the gut microbiome, which plays a key role in regulating our immune responses and controlling systemic inflammation.

The Gut Microbiome and Multiple Sclerosis – What the Science Says

The Gut Microbiome and Multiple Sclerosis – What the Science Says

Recent research has highlighted distinct differences in the gut microbiota of individuals with MS compared to healthy controls. This includes alterations in the composition of gut microbial communities as well as changes in the types of metabolites that these microbes produce. Let’s take a closer look at what the science says:

Dysbiosis in MS

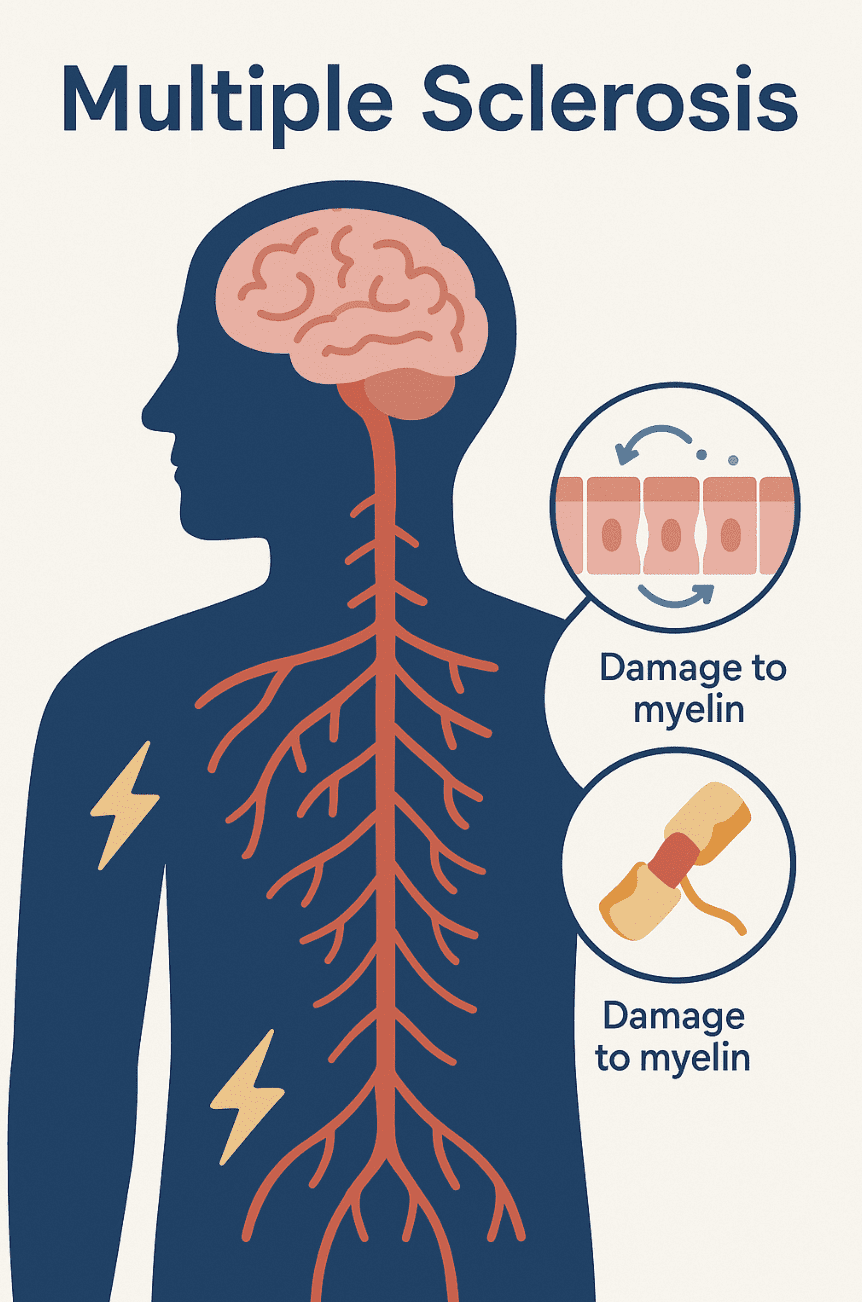

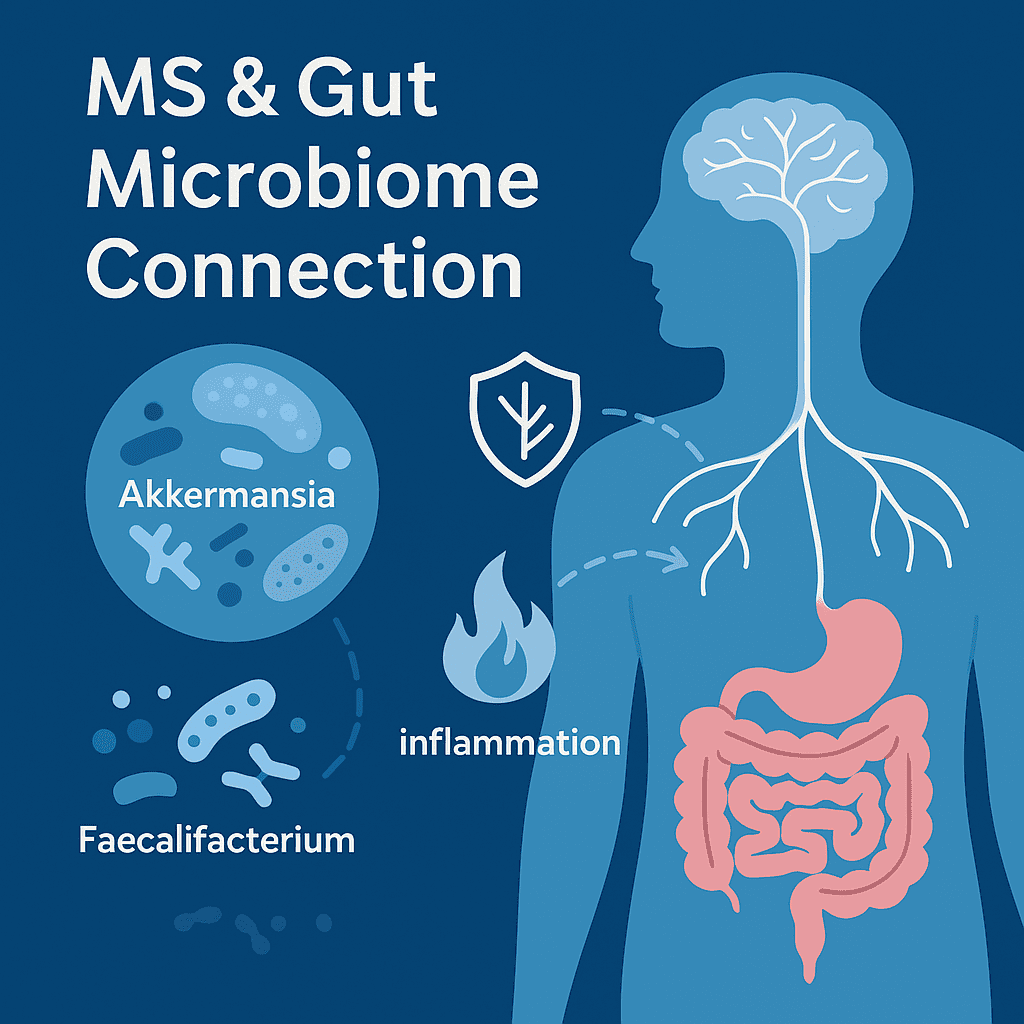

A consistent finding across numerous studies and reviews in this area is the presence of gut dysbiosis in individuals with MS. Reflecting this, a systematic literature review, published in 2023, highlighted key bacterial species which likely play a role in the pathogenesis of MS, including Pseudomonas, Mycoplasma, Haemophilus, Blautia, Dorea, Faecalibacterium, Methanobrevibacter, Akkermansia, and Desulfovibrionaceae (1).

Research studies have shown specific microbial shifts in MS patients. For example, in the International Multiple Sclerosis Microbiome Study (iMSMS), which compared the gut microbiome of 576 MS patients with genetically unrelated healthy household controls, researchers identified significantly increased levels of Akkermansia muciniphila, Ruthenibacterium lactatiformans, Hungatella hathewayi, and Eisenbergiella tayi and a decrease in the numbers of Faecalibacterium prausnitzii and Blautia species in MS patients (2).

Likewise, patients with both relapsing/remitting MS and progressive MS have been shown to have elevated levels of Clostridium bolteae, Ruthenibacterium lactatiformans, and Akkermansia and decreased Blautia wexlerae, Dorea formicigenerans, and Erysipelotrichaceae CCMM (3). In addition, patients with progressive MS had increased Enterobacteriaceae and Clostridium g24 FCEY and decreased Blautia and Agathobaculum. Interestingly, some types of Clostridium bacteria were linked to worse disability and fatigue, while increased Akkermansia was linked to less disability, suggesting it might actually be helpful in MS (2).

Further evidence detailing these microbial shifts comes from a study published recently in March 2025, which showed that patients with untreated, newly diagnosed multiple sclerosis had a significant reduction in gut bacteria coated with immunoglobulin A (IgA), compared to healthy controls. There were also notable changes in specific gut bacterial populations among MS patients. For instance, the relative abundance of Faecalibacterium prausnitzii was diminished, which was consistent with prior research. Conversely, Monoglobus pectinyliticus demonstrated an increased relative abundance and prevalence.

The Role of Microbial Metabolites

The changes in gut bacteria composition seen in MS are important because these microbes actively produce a vast array of metabolites as they digest food and perform their functions. These metabolites act like signals that can be absorbed into the bloodstream, travel throughout the body, and influence various processes, particularly immune and inflammatory responses.

A key group of beneficial metabolites produced by gut bacteria are short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), such as butyrate, propionate, and acetate. SCFAs are vital for maintaining a healthy gut lining, possess anti-inflammatory properties, and help to regulate the immune system. Notably, studies frequently report lower levels of SCFAs and the bacteria that produce them in individuals with MS compared to healthy controls (5,6,7) These changes may potentially contribute to the inflammatory environment associated with MS.

How Does the Gut Influence MS?

How Does the Gut Influence MS?

As the gut is intricately linked to many parts of the body, it can influence MS through several key pathways, which we will explore below:

Gut-Brain Axis

A two-way communication network exists between our gastrointestinal tract and central nervous system. In the context of MS, a dysbiotic gut environment can send signals via these pathways that may promote inflammation within the brain, influence the activity of immune cells in the CNS, and potentially affect the integrity of the blood-brain barrier (8).

Immune System Modulation

Around 70-80% of the body’s immune cells reside in the gut (9) and gut microbes are in constant dialogue with these, playing a crucial role in their development, training, and function. When our gut microbiome becomes imbalanced, this can impair immune regulation, leading to overactive immune responses or inflammation, which is characteristic of MS.

How Could Adjusting the Gut Microbiome Benefit MS?

Adjusting the gut microbiome through diet presents a promising approach in supporting the management of Multiple Sclerosis (MS), as diet is one of the most effective tools to influence both the composition and functionality of gut bacteria. Scientific research increasingly shows that gut dysbiosis — an imbalance in the gut microbial community — may contribute to MS progression by disrupting gut barrier integrity and promoting systemic inflammation. A healthy gut microbiome supports the production of beneficial metabolites such as short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), like butyrate, which help maintain the gut lining’s protective function. When this barrier is compromised due to reduced SCFA production, harmful substances including bacterial components and undigested food particles can pass into the bloodstream, triggering immune responses and systemic inflammation — mechanisms closely linked to the autoimmune activity seen in MS (10).

Moreover, another key mechanism by which the gut microbiome may influence MS is through molecular mimicry. Certain bacterial species, when overrepresented in an imbalanced gut, may produce molecules that closely resemble components of human tissues, particularly the myelin sheath that insulates nerve fibers. This resemblance can mislead the immune system into attacking the body’s own myelin proteins, contributing to neurodegeneration in MS. Research has demonstrated similarities between microbial components from bacteria such as Lactobacillus and Clostridium and human myelin proteins like myelin basic protein (MBP) and myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG). This further supports the potential of targeted microbiome modulation strategies — particularly through personalized nutrition — in helping to reduce MS-related inflammation and slow disease progression.

How Could Adjusting the Gut Microbiome Benefit MS?

Diet is one of the most powerful tools we have to influence our gut microbial communities, including which bacteria are present in our gut and their functioning. Indeed, numerous scientific studies consistently highlight the promising effect that diet can have on MS disease activity and progression (11,12,13)

In order to optimize the potential impact that diet can have on MS patients, it is important that we fully understand an individual’s specific microbial landscape. Personalized nutrition, guided by microbiome analysis, can help to achieve this tailored approach. Instead of providing patients with broad dietary recommendations, microbiome testing helps to inform tailored diet plans. This targeted dietary and lifestyle advice can help to encourage the growth of beneficial bacteria, boost the production of helpful metabolites and rebalance the gut towards a more favorable overall microbial community.

Personalizing MS Management with ENBIOSIS

Managing MS is a complex journey, usually requiring an approach which combines medical treatments, lifestyle and dietary adjustments, and other supportive strategies. As discussed in this article, the gut microbiome is considered a key contributor to the inflammatory processes seen in MS. And so, diet may be an important modulator of the condition, as it directly influences the gut microbiome.

At Enbiosis, we offer advanced gut microbiome analysis using cutting-edge sequencing technology combined with sophisticated AI-powered algorithms. This allows us to generate a detailed picture of an individual’s unique gut ecosystem, which we translate into practical and actionable personalized nutrition recommendations.

Visit our website to find out more about Enbiosis’s approach, or contact us via our contact page if you have any specific questions.

Learn MoreReferences:

1. Dunalska, A., Saramak, K., & Szejko, N. (2023). The Role of Gut Microbiome in the Pathogenesis of Multiple Sclerosis and Related Disorders. Cells, 12(13), 1760.

2. Zhou, X., Baumann, R., Gao, X., Mendoza, M., Singh, S., Katz Sand, I., Xia, Z., Cox, L. M., Chitnis, T., Yoon, H., Moles, L., Caillier, S. J., Santaniello, A., Ackermann, G., Harroud, A., Lincoln, R., Gomez, R., González Peña, A., Digga, E., … Baranzini, S. E. (2022). Gut microbiome of multiple sclerosis patients and paired household healthy controls reveal associations with disease risk and course. Cell, 185(19), 3467–3486.e16.

3. Cox, L. M., Maghzi, A. H., Liu, S., Tankou, S. K., Dhang, F. H., Willocq, V., Song, A., Wasén, C., Tauhid, S., Chu, R., Anderson, M. C., De Jager, P. L., Polgar-Turcsanyi, M., Healy, B. C., Glanz, B. I., Bakshi, R., Chitnis, T., & Weiner, H. L. (2021). Gut Microbiome in Progressive Multiple Sclerosis. Annals of Neurology, 89(6), 1195-1211.

4 Gupta, V. K., Janda, G. S., Pump, H. K., Lele, N., Cruz, I., Cohen, I., Ruff, W. E., Hafler, D. A., Sung, J., & Longbrake, E. E. (2025). Alterations in gut microbiome-host relationships after immune perturbation in patients with multiple sclerosis. Neurology: Neuroimmunology & Neuroinflammation, 12(2).

5. Levi, I., et al. (2025). Potential role of indolelactate and butyrate in multiple sclerosis revealed by integrated microbiome-metabolome analysis. Cell Reports Medicine, 2(4), Article 100246.

6. Ling, Z., Cheng, Y., Yan, X., Shao, L., Liu, X., Zhou, D., Zhang, L., Yu, K., & Zhao, L. (2020). Alterations of the Fecal Microbiota in Chinese Patients With Multiple Sclerosis. Frontiers in Immunology, 11, 590783.

7. Moles, L., Delgado, S., Gorostidi-Aicua, M., Sepúlveda, L., Alberro, A., Iparraguirre, L., Suárez, J. A., Romarate, L., Arruti, M., Muñoz-Culla, M., Castillo-Triviño, T., Otaegui, D., & Microbiome Study Consortium, M. S. (2022). Microbial dysbiosis and lack of SCFA production in a Spanish cohort of patients with multiple sclerosis. Frontiers in Immunology, 13, 960761.

8. Parodi, B. (2021). The Gut-Brain Axis in Multiple Sclerosis. Is Its Dysfunction a Pathological Trigger or a Consequence of the Disease? Frontiers in Immunology, 12, 718220. Wiertsema, S. P., Garssen, J., & J Knippels, L. M. (2021).

9. The Interplay between the Gut Microbiome and the Immune System in the Context of Infectious Diseases throughout Life and the Role of Nutrition in Optimizing Treatment Strategies. Nutrients, 13(3), 886.

10. Bigdeli, A., Ghaderi-Zefrehei, M., Lesch, B. J., Behmanesh, M., & Arab, S. S. (2024). Bioinformatics analysis of myelin-microbe interactions suggests multiple types of molecular mimicry in the pathogenesis of multiple sclerosis. PLOS ONE, 19(12), e0308817.

11. Stoiloudis, P., Kesidou, E., Bakirtzis, C., Sintila, A., Konstantinidou, N., Boziki, M., & Grigoriadis, N. (2022). The Role of Diet and Interventions on Multiple Sclerosis: A Review. Nutrients, 14(6), 1150.

12. Nan, H. (2024). Causal effects of dietary composition on multiple sclerosis risk and severity: A Mendelian randomization study. Frontiers in Nutrition, 11, 1410745.

13. Krivić, A. D., Begagić, E., Hadžić, S., Bećirović, A., Bećirović, E., Hibić, H., Lihić, L. T., Vukas, S. K., Bečulić, H., Kasapović, T., & Pojskić, M. (2025). Unveiling the Important Role of Gut Microbiota and Diet in Multiple Sclerosis. Brain Sciences, 15(3), 253.

Alzheimer e Disbiose Intestinal: O Que Diz a Ciência?

Alzheimer e Disbiose Intestinal: O Que Diz a Ciência? Restaurar o Microbioma Intestinal Pode Ajudar a Proteger o Cérebro?

Restaurar o Microbioma Intestinal Pode Ajudar a Proteger o Cérebro? A Abordagem da Enbiosis para a Saúde Cerebral Baseada na Ciência

A Abordagem da Enbiosis para a Saúde Cerebral Baseada na Ciência